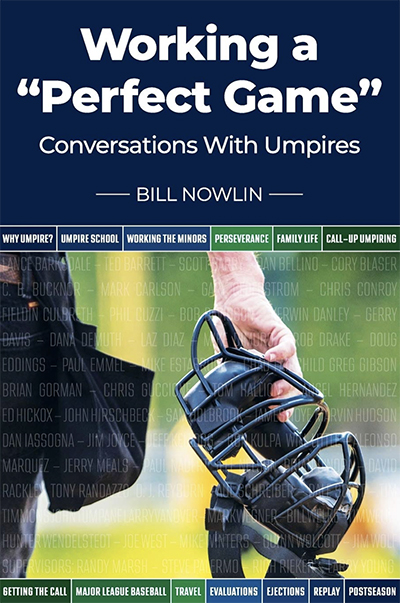

Bill Nowlin. Summer Game Books. May 29, 2020.

Baseball fans “get to know” stars of the game, their favorite players, and even the entire rosters of their favorite teams. We know their stats, learn about their lives, and cheer for them on the field.

But along with players on the field are the umpires, who are essential parts of the game. Umpires keep the game moving and insure play on the diamond is according to the rules of baseball. They are the arbiters, who make the rulings. But how much do we know about the umpires who preside over Major League Baseball games? Not much! An old umpire cliché has it: “If no one notices you, you did a good job” (228). Umpires do not want to be noticed. “Invisibility” is their goal. When that is achieved, they feel they have run the game as well as possible.

Now we have a chance to hear from 87 umpires. Veteran baseball writer Bill Nowlin has given us a fascinating account of his interviews with umpires over the course of several years. We hear the umps in their own words describe many dimensions of being a Major League  Umpire. Their unique journeys—from varied backgrounds—lead them through “Umpire School” and on to two memorable “calls”: The invitation to work a major league game; and the call informing you that “you are being officially hired as a member of the major league staff” (216). Working one’s way up through the minor league ranks takes time—often more than ten years. So, write Nowlin, “given the years and years of devotion, and evaluation, and sacrifice, both are life-changing events and understandably extremely emotional. Every umpire remembers the call” (216).

Umpire. Their unique journeys—from varied backgrounds—lead them through “Umpire School” and on to two memorable “calls”: The invitation to work a major league game; and the call informing you that “you are being officially hired as a member of the major league staff” (216). Working one’s way up through the minor league ranks takes time—often more than ten years. So, write Nowlin, “given the years and years of devotion, and evaluation, and sacrifice, both are life-changing events and understandably extremely emotional. Every umpire remembers the call” (216).

Umpire. Their unique journeys—from varied backgrounds—lead them through “Umpire School” and on to two memorable “calls”: The invitation to work a major league game; and the call informing you that “you are being officially hired as a member of the major league staff” (216). Working one’s way up through the minor league ranks takes time—often more than ten years. So, write Nowlin, “given the years and years of devotion, and evaluation, and sacrifice, both are life-changing events and understandably extremely emotional. Every umpire remembers the call” (216).

Umpire. Their unique journeys—from varied backgrounds—lead them through “Umpire School” and on to two memorable “calls”: The invitation to work a major league game; and the call informing you that “you are being officially hired as a member of the major league staff” (216). Working one’s way up through the minor league ranks takes time—often more than ten years. So, write Nowlin, “given the years and years of devotion, and evaluation, and sacrifice, both are life-changing events and understandably extremely emotional. Every umpire remembers the call” (216). The logistics of being a MLB umpire are not easy. Among the “challenges” that accompany the job is the basic task of getting “from here to there.” While ball teams have homestands that can last up to ten or eleven days, umpiring crews are on the go for each and every series of games. They have to plan their travels, fly on multiple flights, and live in multiple hotel rooms. Umpire Ron Kulpa commented: “The toughest part of our job is the travel. Tomorrow I wake up at 4:00 A.M. The teams are lucky. They get to fly out on a charter, but we’re going tomorrow at the crack of dawn. That’s probably the hardest part” (228).

Other smaller things emerge in these interesting accounts. For instance, Tim Timmons said: “When you’re out with a crew after a game and something has happened, or something hasn’t happened, and somebody says, ‘Hey, are you guys the umpires?’ It’s either, ‘Hey, buddy, we’re not in our umpire uniforms’ or, typically, the one that shuts them down is, ‘What are you, a gambler? Did you lose some money on the game?’ And they’ll leave” (110).

Umpires relish anonymity because they want to be fair and to call a game that does not involve the umpires! As one umpire said: “You want to be absolutely perfect, and we all know that’s impossible. As an umpire, the excitement is when no one notices you” (99).

To approach this goal, umpires need to keep a clear mind. “Focus is essential,” writes Nowlin; “anticipation might be tempting, but is not something an umpire can afford” (275). The basics and the mechanics have to be learned and adhered to, in every game. All this is to enhance the game of baseball, to which the umpires who work the game, have a strong commitment. As umpire Angel Hernandez said: “If you decide to do this work, you’re not doing it to draw people to you, to like you. You’re doing it because of something you feel in your heart. How many people are able to do for a living what they really have in their heart?” (277).

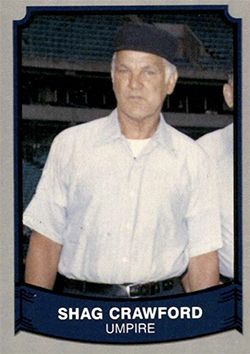

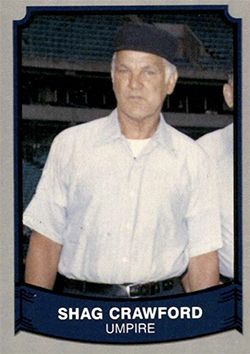

This love of baseball has been passed on to umpires from relatives who had previously been in the profession. Consider: “Jerry Crawford (4,371 games from 1976-2010) was the son of Shag Crawford (3,120 games, from 1956-75), a Crawford thus working games for more than  50 years, from 1956 through 2010. And there were the Runges, a three-generation umpiring family who worked a total of 7,399 games: Ed (2,639 games, 1954-70), his son Paul (3,196 games, 1973-97), and Paul’s son Brian (1,564 games, 1999-2012). As with the Crawfords, there was no overlap” (190).

50 years, from 1956 through 2010. And there were the Runges, a three-generation umpiring family who worked a total of 7,399 games: Ed (2,639 games, 1954-70), his son Paul (3,196 games, 1973-97), and Paul’s son Brian (1,564 games, 1999-2012). As with the Crawfords, there was no overlap” (190).

50 years, from 1956 through 2010. And there were the Runges, a three-generation umpiring family who worked a total of 7,399 games: Ed (2,639 games, 1954-70), his son Paul (3,196 games, 1973-97), and Paul’s son Brian (1,564 games, 1999-2012). As with the Crawfords, there was no overlap” (190).

50 years, from 1956 through 2010. And there were the Runges, a three-generation umpiring family who worked a total of 7,399 games: Ed (2,639 games, 1954-70), his son Paul (3,196 games, 1973-97), and Paul’s son Brian (1,564 games, 1999-2012). As with the Crawfords, there was no overlap” (190). Devotion to baseball took visible shape with umpire Brian Gorman’s father, Tom Gorman, who was a MLB umpire from 1951 until 1976. Tom Gorman had notably said: “When I go, I want to be buried in my umpiring suit, holding my indicator.” Says Nowlin: “And he was” (189).

In the Foreword to this book, writer Larry Gerlach, who had written The Men in Blue: Conversations With Umpires (1980), notes that in this collection of umpire interviews, “there is, alas, an unavoidable omission: the experiences of female umpires. To date only males have reached the major leagues, but that will eventually change given the growing number of women going to umpire schools and working in the minor leagues” (ix). So, Nowlin’s book is a look at umpires who were interviewed in this current period, from 2015-2019. But, as Gerlach rightly says, “this unique and timely book about the lives and experiences of present-day arbiters is destined to become a classic of baseball literature. It will forever change how readers view baseball games and umpires (x).

“Play ball!”

Germantown, Tennessee