Welcome to another edition of Saber rattling. It’s that time. Baseball time is here. Everybody knows there’s not a better time of year. Hear that ump; the pitcher’s on the bump—hip-hip-hooray for spring training baseball.

That’s my underwhelming rendition of Mavis Staples’ title song from the iconic movie Christmas Vacation. I still get giddy each March as the calendar gives way to actual games—even if they don’t count on the back of playing cards. If I’m honest, that’s where my excitement fizzles out.

Don’t get me wrong; I still hope my Royals will threaten to be competitive—past Memorial Day. All the same, I can’t shake the weird game of chicken that marked the off-season between management and players. Both sides blinked, and we were left with a handful of changes to the business side of things and the game on the field. For today, I’d like to dive deeper into the head-scratcher that is the now-universal designated hitter rule.

The universal DH is not without precedent. In the strange experiment that passed for American professional baseball in 2020, MLB suits quietly implemented a trial run of the universal DH. The premise for the change was to keep from overtaxing NL pitchers—allegedly. Fast forward to the 2021 season, and the nine-spot (read: pitchers and pinch hitters) in the Senior Circuit held their own. In fact, the differences in on-base percentage, slugging, strikeouts-per-nine-innings, and errors-per-game were exceptionally unexceptional.

But that’s not what is sold if you read editorials about the rule change. Warnings abound of waning viewership. Some publications have already proclaimed the universal DH as baseball’s panacea for lackluster scoring. Kyle Glaser of Baseball America trotted out pitchers’ offensive triple slash-line from 2021 as evidence of the need for the rule change. He went on to claim the new rule “stands to bolster offense league-wide,” yet offered no evidence.

So, what does the data say about the designated hitter disparity between “professional hitters” and ‘pitchers who can’t hit?’

I’m glad you asked. The designated hitter became a fixture in 1973. Minus the 2020 season, the advent had a forty-eight-year lifespan. It yielded a robust sample of 90,000+ DH team-games alongside a control group the same size. If what we’ve been told is true, the American League should hold a noticeable advantage in offense, fewer strikeouts, and fewer errors since they feasibly get to remove their worst defensive player from the field.

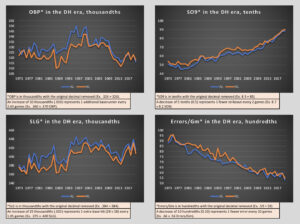

Over the life of the designated hitter experiment, AL hitters enjoyed a boost of five-thousandths (0.005) in on-base percentage. If you’re unsure what that means on a per-game basis, it translates into an additional base runner…every five games. Surely, though, those professional designated hitters out-slugged their pitcher/pinch-hitter counterparts in the NL…

Right?

Well, AL hitters did out-slug the National League—by fourteen-thousandths (0.014). That translates into an additional extra-base hit (via a double) every 72 at-bats. Based on the traditional average of 38 at-bats per team per game, it’s an extra double every 1.9 games. The same milquetoast trends continue with strikeouts and errors. American League batters struck out one fewer time every 3.3 games. AL fielders committed one fewer error every 32 games.

The disparity between the haves and have-nots simply doesn’t exist. Having an additional professional hitter didn’t make the American League noticeably better in any meaningful way. Moreover, the gap has been getting smaller. Since 1998, the AL barely leads the NL in OBP (.329 v .327), SLG (.422 v .412), SO9 (7.1 v 7.4), and errors-per-game (0.62 v 0.63). Even when we break the DH experiment into smaller samples, the gaps are still meh.

The DH-gap was at its height from 1982 to 1997. During that interlude, the AL advantage amounted to one additional baserunner every 2.4 games; one additional extra-base hit via a double every 1.2 games; one fewer strikeout every 2.5 games; and one fewer error every 16 games.

The only conclusion I can draw directly from the data is that National League managers knew they had one fewer bat in their lineup each night and made sure to employ strategies to compensate. Or, viewed from the pessimistic perspective, it could also mean that American League managers were reluctant to pinch-hit for their designated hitters. Either way, it highlights the lack of data to support claims that the universal designated hitter will bolster offense around the league. Please don’t take my word for it. These charts speak for themselves—as does the data table attached at the end of this article.

What, then, are we to make of the now-universal designated hitter?

An article on MLB.com from David Adler probably sums it up best as “good news” for free agents “who are still on the market.” I appreciate Adler’s honesty. If the change is for no other reason than to employ a dozen or so aging hitters who would otherwise be out of the Bigs, so be it. I can live with that—but let’s not pretend this was anything more than a facelift to make baseball feel prettier.

Of course, what lament of the rule change would be complete without referring to Shohei Ohtani and his prowess as a two-way player? This article makes an interesting suggestion that with the universal DH, teams should be able to assign their pitcher as DH if they so choose. I suspect this is such a unique circumstance that it may be years or more before we reencounter this dilemma.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this column. I want to challenge your thinking about baseball statistics. Someday, my own research on the game will become outdated. Please feel free to spar with me about the ideas I’ve presented here—I enjoy the discussion because it challenges my thinking. I can be reached here on Baseball Almanac, and I’m on the social media (Facebook, Twitter). As always, this has been the World According to Chris. Thanks for tuning in.